Where did Vitaly Borodin come from, who helps him, and why does he slander?

Читайте в Телеграм

On December 1, 2025, in Yekaterinburg, OBOP officers, supported by SOBR, detained Vidadi Mustafayev—a man who, only yesterday, had publicly denounced criminal activity in his local communities and claimed to be the new leader of the Azerbaijani diaspora in the Urals.

His face had appeared in the media, and his rhetoric about "clean ranks" was well known to those following so-called "civil anti-corruption activities."

But this time, he found himself accused of large-scale fraud. And this arrest exposed more than just the criminal case of one man. It exposed an entire system of which Mustafayev was only a visible part—the Federal Project on Security and the Fight against Corruption (FBPK) and its founder, one of its most prominent "fighters," Vitaly Borodin.

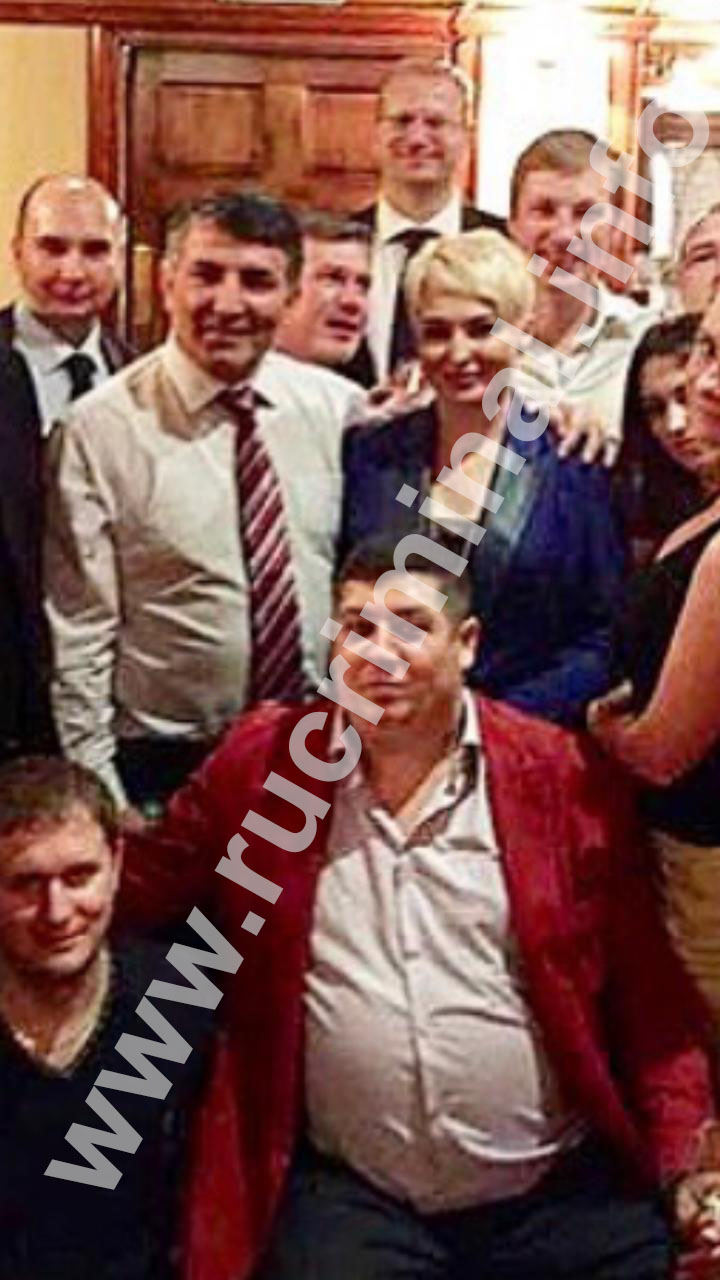

Following the arrest of the previous informal leader of the diaspora, Shahin Shykhlinski, Mustafayev positioned himself as a force capable of restoring order. He spoke of integration, criticized the "hotbed of crime," and assumed the role of a purifier. His main public legitimation was his position as the representative of the Federation of Professional Fighters against Corruption (FPBC) in the Urals Federal District, a structure headed by Vitaly Borodin. Mustafayev positioned himself as someone extremely close to Borodin, his representative.

However, according to the official order to initiate criminal case No. 10784 dated November 21, 2025, signed by Lieutenant of Justice N.S. Bryzgalov, Investigator of the 3rd Department of the Main Investigative Directorate of the Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs for the Sverdlovsk Region, behind the facade of public activity lay something else. The document states that between April and November 2025, Mustafayev, "while in the city of Yekaterinburg, fraudulently stole funds totaling 16 million rubles." This charge of large-scale fraud (Part 4, Article 159 of the Russian Criminal Code) was not the first in his biography—he had previously been prosecuted.

Thus, someone who publicly donned the mantle of a fighter against violations himself found himself at the center of a criminal prosecution for a serious economic crime.

To understand how a regional representative with a criminal past could become the face of an "anti-corruption" organization, the Cheka-OGPU and Rucriminal.info decided to look at its top.

Vitaly Borodin is a well-known and controversial figure in the media. He has a long history of serious administrative violations and "foul-smelling" stories.

For example, in 2017, he was charged under Article 159 of the Criminal Code. Article 20.17 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of the Russian Federation (Violation of Access Control at a Guarded Facility). Using an expired ID card issued by the assistant to the head of Ingushetia, Borodin attempted to enter a guarded facility. He was stopped by the Federal Protective Service (FSO) and sentenced to 15 days of administrative arrest. This incident was later masterfully integrated into his public myth, transforming from a violation into a "scar on the body of an anti-regime fighter," which he "sold" to his audience. That same year, on December 23, he received another administrative arrest for a detention report in Moscow. He had previously been charged under Part 5 of Article 19.3 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of the Russian Federation (Disobedience to a Lawful Order of a Police Officer).

Borodin was forced to resign as deputy head of the Solnechnogorsk administration after his subordinate was detained accepting a bribe of 1.2 million rubles. Moreover, this bribe was traced higher up the chain of command... But it all ended with his dismissal.

Borodin was also noted for his connections to the notorious Elman Pashayev. As the Cheka-OGPU reported, singer Katya Lel introduced Elman Pashayev and Vitaly Borodin. Both are involved in scams and con-artistry. After being fired from the Solnechnogorsk administration in the Moscow region, where he held the position of deputy head of the administration for security, he decided to become a lawyer to qualify for special subject status. His friend and partner, Pashayev, helped him. Like Pashayev, Borodin illegally obtained a lawyer’s license because he did not and does not reside in Ossetia, had no business there, etc.

Borodin attempted to intervene in Mikhail Efremov’s criminal case as the injured party and represent the interests of Irina Sterkhova, the common-law wife of the deceased Sergei Zakharov. Had Irina Sterkhova not refused Vitaly Borodin’s services, the scheme to extort money from Mikhail Efremov would have been very effective. Two friends, Elman Pashayev, defending the accused Mikhail Efremov, and Vitaly Borodin, representing the injured party, both members of the same Bar Association in the Republic of North Ossetia-Alania, were planning a grand scam using the money of the embattled Mikhail Efremov.

And this unusual figure, a former operative and civil servant with a background in law enforcement, created the FPBC, which subsequently became known not for its investigations, but for its massive public campaigns. The organization regularly submits petitions to law enforcement agencies demanding investigations or prosecutions of media personalities—from artists to journalists. Borodin himself positions himself as an uncompromising fighter against corruption and "foreign influence," often Speaking on federal television channels as an expert.

However, the methods and effectiveness of this fight raise questions. In 2023, Borodin lost a lawsuit to actor Danila Kozlovsky, who had ordered him to pay a symbolic one ruble for defending his honor and dignity. This ruling called into question the credibility and validity of his public accusations. Furthermore, experts have repeatedly pointed out that the FPBC’s model of public "denunciations" through the media can be used not for human rights protection, but as a tool of pressure or a means of waging commercial and political conflicts. The selection of regional representatives also deserves special attention.

The connection between Borodin and Mustafayev was never a secret. On the contrary, Mustafayev actively used his status as a representative of the FPBC to bolster his public image. This connection was part of their overall strategy.

Mustafayev’s story extends beyond the current criminal case. He previously headed the Vozrozhdenie Foundation, which in 2022 received a 2,742.9 square meter building in Yekaterinburg from the state for free use. The foundation was subsequently declared bankrupt by the Sverdlovsk Region Ministry of State Property due to misuse of the property. Thus, a man representing an organization professing to fight corruption found himself directly implicated in a scandal involving the misuse of state property.

Mustafayev also acted as an intermediary in the transfer of funds from the former mayor of Sredneuralsk, testifying in this criminal case. This "intermediary" experience raises a legitimate question about the real nature of the activities that may have been conducted under the guise of loud slogans.

Mustafayev’s situation reveals a profound internal contradiction that can be described as "institutional hypocrisy."

Fighting corruption for everyone but our own? While the FPBC demands audits and punishments for a wide range of individuals, its own Ural representative has been accused of large-scale fraud. The question naturally arises: did the FPBC leadership conduct any internal audits of the activities of its regional appointees? Or was the public status of "fighter" considered sufficient indulgence?

The FPBC’s key method is mass appeals to law enforcement agencies. Formally, this is civic activism. But in practice, as individual cases demonstrate, this system can be used to attack competitors or resolve private disputes. This creates the risk of turning state institutions into a tool for pursuing someone’s interests.

Borodin’s public position is based on a staunch rejection of any foreign influence. However, biographical materials published by a number of outlets (for example, Deutsche Welle) contain information that in a 2020 interview with TV-Tver, Borodin thanked the American National Endowment for Democracy (NED), later designated an undesirable organization in Russia, for funding his studies. Borodin later publicly denied giving such an interview. However, TV-Tver journalists claim the interview took place and that Borodin himself requested its deletion. The very fact that such questions have arisen regarding the biography of the leading "fighter against foreign influence" is symbolic. It demonstrates how fragile the line between public image and personal history can be.

The arrest of Vidadi Mustafayev is not just an episode in the police reports. It is a symptom of a systemic problem.

Such stories seriously damage trust. They discredit the very idea of civil anti-corruption oversight, replacing it with projects with unclear funding, opaque internal structures, and representatives whose reputations cannot withstand scrutiny. The state risks being drawn into resolving private conflicts under noble slogans.